Back in Bogotá, Colombia, I was always «the smart one.» I built my ego around that. When I went to school for the first time, at 7, my teachers had me skip one grade within the first week. As I was growing up, on tenth and eleventh grade (what you call in the United States secondary school) my friends ended up being the professors and not the girls of my cohort. I was able to connect with the teachers because I sustained intelligent conversations with them, so we bonded.

After graduating, I studied Philosophy. In Colombia, we don’t have majors; you pick a career since the beginning and study for 4 or 5 years all about that discipline. In Philosophy, I was in a mostly masculine environment, and I did extra work for them to never think I wasn’t good enough based on my gender. I exceeded there and I even co-led the student’s publication journal. Parallel to Philosophy, I started Literature Studies in a different university. At that time, double majoring was not a thing. And again, I felt very intelligent because I was older than the others.

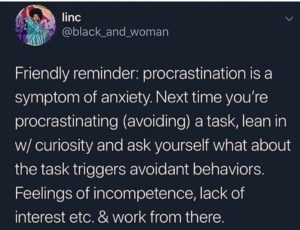

When I landed in the US, I was not smart anymore. I never communicated my thoughts in English or heard people speaking English beyond my illegal hamburger server job in Miami. I was terrified. There where so many words I didn’t understand when I was listening. And all the authors I knew had names pronounced differently. I was paralyzed. I had this recurrent feeling of getting tired in the middle of the day, like I wanted to lie down in the floor, really, because when you try to pay attention for a prolonged time to a new language, you get drained.

At some point, in my second semester, a professor refused to read my paper because it had grammatical mistakes, and I got depressed and anxious, and I cried a lot. Money issues at that time (and at all times, honestly, as a graduate student) were pressing. I felt I was going to fail but, if I were to drop the class, I would lose my scholarship and then I would not be able to stay. A lot of international students like me have an extra pressure from our home countries to succeed. In my case, besides the fear of failing and confess the truth to everyone that had told me “good bye, siri, you’re a winner and see you in 7 years”, there was also the fact that my mom had given me her lifelong savings to move out of Colombia.

Rough days kept passing and passing. I found some other Latinx students that I could talk to and felt similar to me. I started to heal, to pray, to love myself better. Somehow, I discovered I don’t need (as if my life depends on it) to be the smart one. And I am more than the smart one. And yet I am smart, I’m damn smart, damn it.

Little by little, I recovered my confidence. I learned that a lot of the academia dynamics makes a lot of us (international or not) feel not good enough. Academia is certainly NOT diverse. There is a particular pace for learning, for communicating, for writing, and everyone outside of that is “failing”, or so we might feel. In this journey, I also learned to stay away from people (professors and classmates), who made me feel not smart enough and that had dynamics of power that were not embracing and nurturing my intellect. In that path, I found amazing professors (mostly women of color) who made me feel heard and validated my knowledge.

Little by little, I became proficient in my verbal communication and in my writing (not so much this one, though). My brightness came back to me. Now, in my third year, I find myself more able to listen to other people’s opinions, to be humbler, to be more open (still working in all that, for sure) because of all I went through. That also shaped my practices as professor of Spanish and Theatre History because I can see how this culture pushes my students to fear that they are not enough, inadequate; a failure. I try to create a loving classroom where we can all learn together and not be perfect without harming our self-esteem. I have also accepted that I am not a perfect student or teacher, and I forgive myself for that as much as I can.

Finally, I can feel successful again and I want to observe my ego to avoid going back to the dynamic of “being ‘smart’ is all that matters—if me, or anyone, is not smart, then that’s a failure.” I want to observe myself with love, to tell myself «all parts of me are welcome here,» so that I can offer that to the others around me. That’s an intention and a prayer.