The Monster Hiding in the Archives: Spanish Paleography and its Secrets

I. What is paleography?

The ability to read and study ancient or historical handwriting styles that are no longer recognizable and familiar to modern readers is called paleography. Those of us who want to work with primary sources that have not been transcribed by historians and other diligent scholars must learn this skill, whether the writing is from the 1960s, the 1850s, or the 1300s.

I first wrote a short piece on paleography in the spring of 2016, as part of a collaborative series on this discipline. At the time, I was new to paleography, and most of my successes and failures stemmed from my firsthand experiences, much embarrassment, and many hours struggling with early modern Spanish texts. What struck me the most was that accessing an archive does not always mean that I will be able to actually read the texts that I proposed to read. Something that no modern reader would expect happens in the archive: time has passed, modern writing styles do not look like the scribbles that you are looking at, the writer was in a rush, the writer used strange writing instruments, the language changed over time, the ink faded… In short, it’s possible to discover that an ability to read modern handwriting and print does not carry over to archival work. In order to read these texts, I had to develop new reading skills. I wanted to write a follow-up piece in order to give early researchers some pointers for where to start learning about paleography and things to consider along the way.

What is paleography good for?

Paleographic ability is critical in the archives, whether or not you are interacting with printed materials. Even in printed works, the texts owned by famous authors and artists often have notes left in the margins, at the beginning, or as a type of colophon; these notes might be cramped or hastily scrawled. With practice, such annotations do not have to contribute to the unknowable mystique of the previous owner of your book: they can be read. Whether you are looking at Christopher Columbus’s careful notes in his copy of Il Milione or Salvador Dalí’s notes in a draft for his cookbook Les Dîners de Gala (1973), paleography allows you to glean insights from these book owners by reading their annotations.

For those who wish to enter careers related to book histories and preservation, many libraries and museums actively seek out curators and archivists that can read the “terrible” handwriting that lurks in their holdings. This skill is an asset for any position in these areas.

Lastly, paleography as a skill is shockingly useful for teaching and working with students. With a well-developed ability to recognize handwriting styles and mechanical patterns, it’s possible to not only read “poor” modern handwriting (eliminating the need to repeatedly contact and annoy students about their work), but it’s also possible to recognize when a student couldn’t decide between A and D on a multiple choice question and elected to test their luck by writing a chimeric letter that could be either an A or a D.

II. Good Paleographic Practices

Paleographic work, in my opinion, brings many different fields together and is truly interdisciplinary. While it is tempting to assume that knowing the alphabet of the text you want to read and having reading or speaking knowledge of the language is enough, it’s not. Over my time in the archives, as well as a lot of exposure to failure, I’ve listed here what I think are some of the key areas to be aware of when diving into a text and flexing your paleographic muscles.

Be multilingual, or, at the very least, think about it.

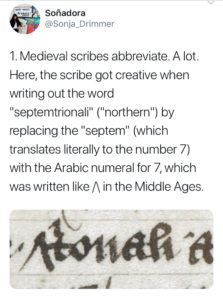

If the author or owner of the text was a polyglot, as many people historically have been, a savvy paleographer will expect to see all of these languages appear in their text. While this may not be such a big deal with modern latinate texts (Spanish and French have much linguistic overlap and perhaps you can work around it), early modern and medieval texts can give any level of scholar quite a lot of trouble. One should expect to see Greek letters and writing, definitely some Latin, possibly some Hebrew and Arabic, and a romance language. One should also expect them to interchange a bit, depending on convenience to the writer.

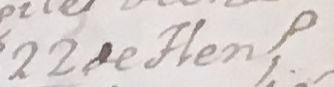

This says “22 de HenΡ” with the Greek letter “rho” or “Ρ.” Pronounced phonetically and relying on context clues, this is an abbreviation for “enero.”

By being aware that many writers used other languages and alphabets in their shorthand, you will already be well on your way to being a successful paleographer. In my next post, I will discuss the use of symbols and phonemes in more detail, explaining what can make Spanish orthography, the way words were spelled, very complicated.

This piece is part of The Monster Hiding in the Archives: Spanish Paleography and its Secrets, a series of articles that explores the discipline of paleography.