I. What is paleography?

The ability to read and study ancient or historical handwriting styles that are no longer recognizable and familiar to modern readers is called paleography. Those of us who want to work with primary sources that have not been transcribed by historians and other diligent scholars must learn this skill, whether the writing is from the 1960s, the 1850s, or the 1300s.

I first wrote a short piece on paleography in the spring of 2016, as part of a collaborative series on this discipline. At the time, I was new to paleography, and most of my successes and failures stemmed from my firsthand experiences, much embarrassment, and many hours struggling with early modern Spanish texts. What struck me the most was that accessing an archive does not always mean that I will be able to actually read the texts that I proposed to read.

After being aware of a few different alphabets that writers could use in their shorthand and knowing how a language’s orthography can vary, researchers also need to take into account the physical and spatial limitations of the writer.

II. Good Paleographic Practices (Continued)

Writerly styles in early modern writing

Early modern writers (and modern writers) used a vast array of writing types, depending on the type of document (courtly, legal, etc.) and their own personal style. These styles range from rather “accessible” writing to the very cramped (Ex. “cortesana” style, like this: http://spanishpaleographytool.org/dsi_documents/agi-justicia-12-num1-ramo2-cabildo-obispo-fo-51r ) or very elongated (Ex. “procesal-encadenada” style, like this: http://spanishpaleographytool.org/dsi_documents/agi-escribania-3a-192v-2 ). In my opinion, the elongated styles have always caused most of my difficulties and the only way to deal with them is to hold the paper very far away from my face or to look at the word indirectly, out of the corner of my eye. It becomes a game of hide and seek with words. The elongated style documents can sometimes take many days for me to read. Apparently I’m also not alone in my dislike for this still and even Miguel de Cervantes had something to say about how unnecessarily difficult the encadenada style is.

In order to gain mastery with these styles, it is important to work with websites like The Dominican Studies Institute at CUNY (http://spanishpaleographytool.org/ ), which allows you to practice with the different writing types and allows you to hover your mouse over each word to discover what it is as you go along. Familiarity breeds success and ease–the more you do it, the easier it is. Once you learn the trends, it becomes much easier to pick up unfamiliar writing styles, the strange swoops of the pen downwards on a “q” and the lazy backslashes of a “j” half-formed. Part of this is actually practicing writing the letters and words yourself; in a class I took with Dr. Jorie Woods, she recommended creating a table to track the visual appearance of each letter as you “discover” it, noting the difference between capitalized, lower case, and end-of-word letter styles.

While these resources are invaluable for training with paleography, it is important to note that in Spanish (and in many other languages), the interest in time-saving and paper-saving led to word abbreviations, some of which can only be known and recognized through memorization and through knowing the context of your text (where/when it was written, by who, and for whom).

The difficulty of abbreviations

Medieval scribes, like early modern writers, sometimes used abbreviations. However, their abbreviations were mostly practical and indicate the missing letter or syllable with a dot or a line over the missing part of the word. Scribes always left enough of the word for the missing letter or syllable to be obvious. In the case of missing syllables, it was usually the syllable at the end of the word.

Early modern Spanish writers and amanuenses–those employed by nobility and other officials to write so that they did not have to–often relied on shorthand to save paper and time. These abbreviations are not always as recognizable to the modern reader, as they are formed by common use and conventions rather than by practicality. In order to read these abbreviations, one must know the written context in which the abbreviation is being used and the grammatical function of the unknown abbreviation in a sentence. For example, the sentence “Pedro me ha dicho que…” could look like any of these:

Pedro me ha dicho que…→ Pro me ha dicho q~…→ Pro me a dho q~… → Promeadhoq~

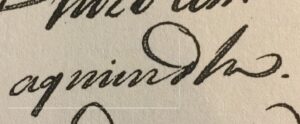

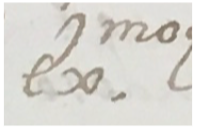

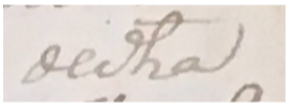

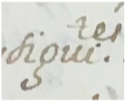

In order to know that “Pro” is an abbreviation for “Pedro,” the reader must be aware that “Pro” is functioning as the subject of the sentence and as a proper noun. The word “ha” transforming into “a” is more obvious due to the fact that the sound of the verb does not change. “Dicho” often loses the “ic” and is one of the most unrecognizable words when written by a scribe, as will be shown below. And, lastly, words like “que” are often abbreviated to various iterations of “q~,” for example:

Que→ q~

Quien→ q~n

Cualquier → qualq~r→ q~lq~r

After gaining experience with these more difficult issues, abbreviations like “ExmoSr” or “ExoSr” in their contexts become the more obvious “Excelentísimo Señor.” My experience with abbreviations has been informed by working with Juan Carlos de Orellana Sánchez’s paleography workshop, which he directed and hosted in conjunction with Dr. Kelly McDonough. It was also informed by volunteering at the Benson Library and working with (and transcribing) some of their New World texts for the Mapping Mexican History travelling exhibition. Lastly, an extremely helpful book with some common abbreviations and helpful vocabulary explanations is Dr. Delia Pezzat Arzave’s Guía para la interpretación de vocablos en documentos novohispanos: siglos xvi-xviii. This link, which goes to BYU’s script tutorial, is also extremely useful: https://script.byu.edu/Pages/the-spanish-documents-pages/sp-abbreviations(english). I recommend taking a look and how many options exist for the word “dicho.”

All three images from G120-20, Genaro García Collection, LLILAS Benson.

To conclude, studying paleography is a process that takes time, dedication, and repeated practice with original source materials. I also regard it as a community effort, as I learned with and among various scholarly groups and serving different institutional needs. By understanding physical, spatial, and stylistic limitations that can force a scribe to compress and contort their writing, one can begin to see that paleography is not an opaque science, but a useful tool for any kind of primary source.

Paleographic Resources

The resources below support new learners of paleography as well as those who wish to explore how certain digital resources can be co-opted into the process of textual transcription.

- BYU’s Script Tutorial: https://script.byu.edu/Pages/the-spanish-documents-pages/sp-abbreviations(english)

- The Dominican Studies Institute: http://spanishpaleographytool.org/

- Christopher de Hamel, Scribes and Illuminators (1992)

- Transkribus, early transcription software: https://transkribus.eu/Transkribus/

- Recogito, for annotating digitized texts: https://recogito.pelagios.org/

- For broader applications, the DiRT Directory of digital research tools: http://dirtdirectory.org/

- The “voice typing” function within google docs, for quick transcribing based on reading aloud.

- Adobe Photoshop, for when ink has faded and you need more contrast: https://helpx.adobe.com/photoshop/using/making-quick-tonal-adjustments.html

- Want to learn more? Apply to the Mellon Summer Institute in Spanish Vernacular Paleography, hosted this year at the Huntington from June 24-July 12, 2019. More information here: https://www.newberry.org/mellon-summer-institutes-vernacular-paleography

- Useful academic blog, which in a few months will also be featuring a paleography game called Littera: http://www.litteravisigothica.com/ . It is run by Dr. Ainoa Castro, a scholar works with Visigothic scripts

Acknowledgements

Archives that have contributed to the sum of my experiences include the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, the Archivo Capitular of the Cathedral of Toledo, the Widener Library at Harvard, the Newberry Library in Chicago, the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid, the LLILAS Benson Library at the University of Texas, the Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto, the Archivo General de las Indias in Seville, and the Library of Congress.

This piece is part of The Monster Hiding in the Archives: Spanish Paleography and its Secrets, a series of articles that explores the archival technique of paleography.