The year is 1998. A couple of days after Christmas. At the Miami International Airport, a 15-year-old kid is called upon by an officer at customs before he’s allowed to enter the United States. The officer looks at him upside down: blonde hair, green eyes, both ears pierced, baggy jeans worn well below the waistline. The man is very serious. He smirks before he starts hollering:

-¡Oye Rafa! ¡Mira quién llegó aquí!

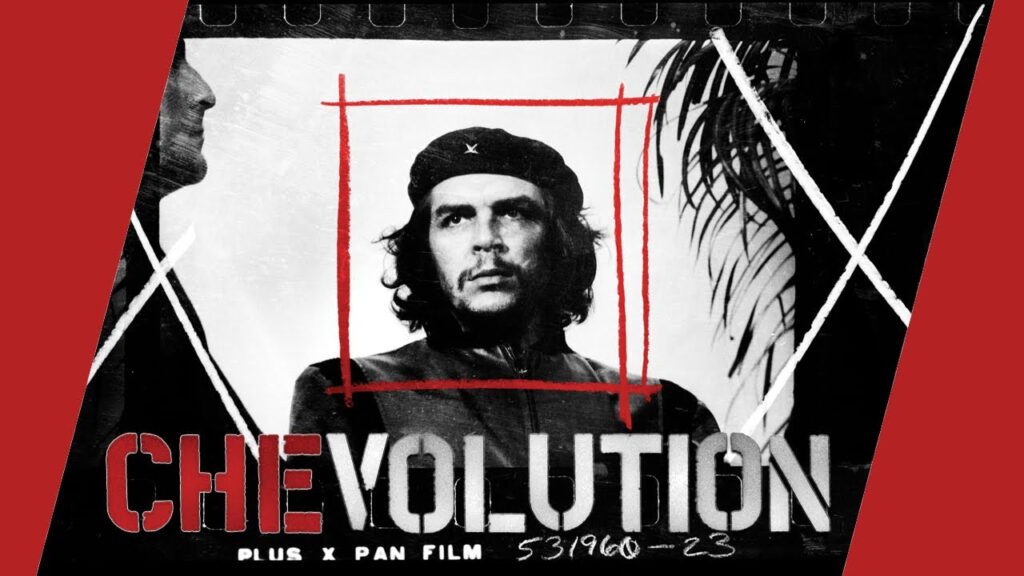

He shouts over his shoulder to a fellow officer. He points at the t-shirt the dumbfounded teenager is wearing: a black cotton t-shirt with the face of the Cuban revolutionary Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara. It is the image of cover of a Rage Against the Machine album.

-Tú no sabes quién es él. ¡Ese es un asesino!”. –The officer speaks in a Caribbean accent. The officer now turns to the boy’s father and reprimands him.—“Y usted. ¡Usted es un irresponsable! Dejar que su hijo ante por ahí vistiendo así y venir acá, a Miami… Le digo una cosa, es menos peligroso ponerlo a caminar por las calles de Miami con una ametralladora Thompson que dejarlo caminar por ahí con esa camiseta del asesino ese. ¡Ha! ¡Este pitico!

The father smiles as he looks at the teenager who has been mute and almost shrinking the whole time the officers lectured him on “his ignorance” for “celebrating a mass murderer”. He goes to the nearest bathroom, comes back a few minutes later a button shirt covering the problematic t-shirt.

The teenager wearing the Che t-shirt was my brother. The story has become part of our family’s remembrance vault and still elicits laughter when told occasionally.

I’ve revisited the anecdote after watching Chevolution, the 2008 documentary directed by Trisha Ziff that explores “the man, the myth [&] the merchandise” around the iconic Che Guevara photograph that Alberto Korda took in 1960.

At one point in the documentary, another photographer talks about the vitality of images and where it comes from: “from what people do with the images”, not from the images themselves. Another voice in the documentary signals our need for icons, legends, and myths. “If we don’t have them, then we have to create them”. A statement that has an echo in a worker interviewed and his assertion that he “doesn’t believe in any God”, but if he did “it would be Che Guevara”.

Guevara’s image came to be a symbol of heroism and courage. That’s part of the magnetism of his image as a symbol. It serves as an unattainable, idealistic, level of commitment to a cause. That archetype, of the one willing to sacrifice everything for his belief system, is attractive.

Perhaps that’s why Alma Guillermoprieto says it was “astonishing fact” that so many wanted to be like him, even while they knew so little about him. However, symbols are not to be questioned or scrutinized. The very system Guevara despised has cashed in on ‘the rebel promise’, in so doing the power of the symbol has faded[1].

Like the Political Science professor Eric Selbin told the Pullitzer Center’s Sarah Caspari, if you’ve reached a point where fast-food chains can use your image for the advertising campaigns, that’s not very good. “The commodification of Che is surreal.” (…) “There’s a level at which Che as a figure is right on the edge of being an empty signifier. You can make him mean whatever you want him to mean”[2].

[1] See: The Harsch Angel. By Alma Guillermoprieto. InLooking for history: dispatches from Latin America. 2001.

[2] https://pulitzercenter.org/education/global-perception-che-guevara