Every few years, an article appears in a newspaper in some corner of the world to break the news: there used to be a strong black presence in Argentina. The last one I read was about a month ago, from the International Business Times, of all places.

If you don’t have time to read it here, this is the gist of it. The author, Palash Ghosh, begins with one of the repeated tropes of racial discussion in Argentina: unlike neighboring Brazil, in Argentina the legacy of slavery is, for the most part, invisible. The other option would have been to use some variation on the phrase: “Negros, en Argentina, no hay”. One of the foundational studies of this field, The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires, by George Reid Andrews, even uses this sensational statement to begin explaining how there are and always have been Afro-descendants in the region. I’ve even used the phrase in a paper. I guess it’s hard not too when those words continue to be spoken on the street today.

Anyway, Ghosh’s article does a good job of explaining how racial categories and the stigma associated with being “black” has eliminated most of the visible African heritage from Argentine culture. However, as the piece mentions briefly, Argentine culture does have hidden African heritage in the tango, many words and foods, especially cuts of meat, that make up some of the country’s most notable tourist attractions and exports.

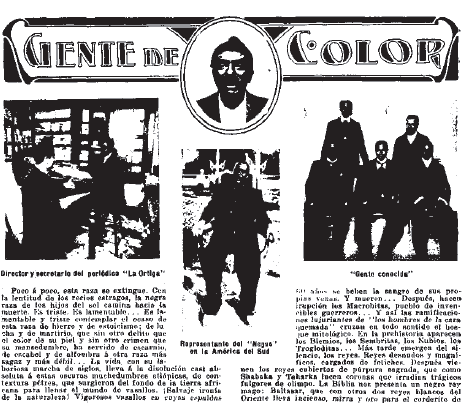

However, like most articles of this type, the author can’t help but lament the disappearance of the black presence in Argentina by the end of the 19th century, stating that: “by 1895, there were reportedly so few blacks left in Argentina that the government did not even bother registering Afro-descendants in the national census.” Census data and the enormous waves of European immigration did much to hide the country’s black presence, but here’s my beef. While Ghosh confirms that they did not actually disappear, but were “hidden and forgotten,”the tone is not very different from the elegiac lamentations of a 1905 article about “La gente de color” in the middle-brow Argentine magazine Caras y Caretas. “Little by little, this race is extinguished,” begins the piece published more than a century ago.

In a hundred years, the place of Afro-descendants in Argentina as a source for fait divers hasn’t much changed. Neither has the mournful tone, which more than anything confirms Argentina’s place as the “whitest” Latin American nation and the atavistic position of Afro-Argentines squarely in the nation’s past.

What both articles ignore (but what Andrew’s now over 30-year-old study recognizes) is the contradiction behind the elegiac façade. In the last decades of the 19th century, just as the censuses were declaring extinct Argentina’s black population, over twenty newspaper and magazines emerged in Buenos Aires alone from and for the black community. The papers, like La Juventud and La Broma, varied by socio-economic standing, political affiliation, and taste, but all showed that the Afro-porteños were an active and integrated community within Buenos Aires.

What does this have to do with tone of the articles? Why would you write an obituary for someone who isn’t yet dead? While census data «proved» the disappearance of the black community, as Andrews discovered, much of the Afro-Argentine community had transitioned to the categories of «blanco» and «trigueño» and passed as white. So the mournful tone of the articles, instead of addressing the racism that would drive Afro-descendants to switch census categories and hide their heritage, leaves touchy subjects untouched and instead, muffles Argentina’s black heritage by burying it alive.