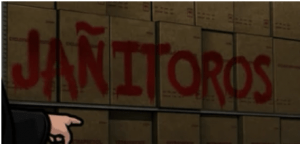

In “Placebo Effect,” an episode in the 2nd season of the critically acclaimed cartoon series Archer, the self-proclaimed “über-German” Dr. Krieger unintentionally reveals that he was raised not in the East Coast suburbs, but in Brazil. The show, created by Adam Reed, is based around the exploits of the incompetent spy agency Isis and the protagonist, Archer, a misogynistic, callous, secret-agent, creating comedic tension based on prejudice, misanthropy and gratuitous violence. While the series rarely engages with Hispanic themes, beyond the occasional derogatory remark to enemy spies or janitors (jañitoros as Archer spells it), a sort of Banana-republicanized Brazil (along with Nazism) become motifs in this episode.

In “Placebo Effect,” an episode in the 2nd season of the critically acclaimed cartoon series Archer, the self-proclaimed “über-German” Dr. Krieger unintentionally reveals that he was raised not in the East Coast suburbs, but in Brazil. The show, created by Adam Reed, is based around the exploits of the incompetent spy agency Isis and the protagonist, Archer, a misogynistic, callous, secret-agent, creating comedic tension based on prejudice, misanthropy and gratuitous violence. While the series rarely engages with Hispanic themes, beyond the occasional derogatory remark to enemy spies or janitors (jañitoros as Archer spells it), a sort of Banana-republicanized Brazil (along with Nazism) become motifs in this episode.  Archer’s poor Portuguese and comments about how much “sexier” a Brazilian mob would be than an Irish one are the typical comedic fare for these vignettes, but they to lead to a more important narrative sub-plot on the mad scientist’s dubious origins. From his slip that he grew up in “Brazistle, Rhode Island,” the nerdly accountant Cyril tricks Dr. Krieger into speaking back to him in German, resulting in a not-so-subtle hint of his upbringing when he yells the phrase “Mein Führer”. Later on, between watching Dr. Krieger burn apparently Nazi-related documents in the toilet and the admission by the director of Isis, who happens to also be Archer’s mother, that she knew all along, the connection between Krieger’s Brazilian childhood and his National Socialist family is solidified. The team comes to the conclusion that oh my god he was one of the “Boys from Brazil,” a reference to the 1978 film by the same name about Nazi-hunting in South America. While this last epiphany maintains the rather self-referential and pop mélange themes that the show is known for, Dr. Krieger is just one example in a substantial corpus of contemporary media that stereotypes German descendants in South America as being Nazis, or children of Nazis, or Nazi sympathizers.

Archer’s poor Portuguese and comments about how much “sexier” a Brazilian mob would be than an Irish one are the typical comedic fare for these vignettes, but they to lead to a more important narrative sub-plot on the mad scientist’s dubious origins. From his slip that he grew up in “Brazistle, Rhode Island,” the nerdly accountant Cyril tricks Dr. Krieger into speaking back to him in German, resulting in a not-so-subtle hint of his upbringing when he yells the phrase “Mein Führer”. Later on, between watching Dr. Krieger burn apparently Nazi-related documents in the toilet and the admission by the director of Isis, who happens to also be Archer’s mother, that she knew all along, the connection between Krieger’s Brazilian childhood and his National Socialist family is solidified. The team comes to the conclusion that oh my god he was one of the “Boys from Brazil,” a reference to the 1978 film by the same name about Nazi-hunting in South America. While this last epiphany maintains the rather self-referential and pop mélange themes that the show is known for, Dr. Krieger is just one example in a substantial corpus of contemporary media that stereotypes German descendants in South America as being Nazis, or children of Nazis, or Nazi sympathizers.

I’m not saying that this contingent doesn’t exist in the Americas (North and South). It does. Just last year files held in Brazil and Chile were released that confirmed the exodus of over 9,000 war criminals – not citizens, war criminals –during the Third Reich, although they were not all from Germany. Argentina’s Perón was notorious for accepting dubiously or directly implicated German migrants in the post-war period, and of course, there is the story that Hitler died in Bariloche. In Chile, Nazi presence is immortalized in the tale of Paul Shafer’s Colonia Dignidad, although it was not the only enclave of that type. But the fact remains that most Germans in South American arrived before World War II, even 100 years or prior in some cases. Let’s look at the numbers briefly. German immigration to Brazil numbered close to 7,000 individuals in the 1940s, and 17,000 in the 1950s. While those aren’t insignificant, the fact that over 100,000 German migrants arrived in the country between 1920 and 1940, and in the century leading to that period, Brazil received about another 100,000, indicates that our ideas of German presence in South America aren’t exactly accurate. However, the all-Germans-are-secretly-Nazis trope is still enough of a box office boon to keep it alive. It sells, despite historical fallacies.

While Archer is not known for its historical accuracy, seeped in a hybrid world of James Bond-esque Cold War espionage and contemporary popular references, the fact that this hit American cartoon series chooses to engage with the Brazilian-Nazi theme proves how lasting and consumable these stories are. Tropicalized Nazi-bashing a la Inglourious Basterds? Based on an online poll which ranks “Placebo Effect” as the top rated Archer episode of all time, I suggest that the exoticism of the Brazilian version of the all-Germans-are-secretly-Nazis myth is what makes it so appealing.

3 comentarios

El mito también dice que Hitler no murió en Bariloche, sino que se encuentra congelado en alguna parte oculta de la gran Cordillera de los Andes. Allí es custodiado por las fuerzas nazis de Chile y Argentina en la espera de del momento adecuado.

Simplemente para sumar referencias la lectura del autor chileno Miguel Serrano retoma la concepción mística del nazismo y les da un nuevo hogar en el extremos sur del continente, lecturas interesantes que también muestran como funcionan las relaciones de política y literatura en los círculos públicos.

Great post Megan. I really enjoyed reading it.

Me recordó a una remota mañana de recreo en pre-Kinder en que aprendí a jugar a la ronda del perro judío… terrible. Hoy me parece increíble pensar en multitudes de niños jugando y ayudando a mitificar a los nazis!

Gracias Paula y James! Tendré que leer algo de Migual Serrano y qué fuerte lo del pre-Kinder.