I’ve been thinking recently about the process of writing syllabi. Inspired by great writing about films on this site by Valeria and Nat , I wanted to look particularly at what it would mean to read Spanish-language literature and film in tandem. Here are two examples of how I think it might work.

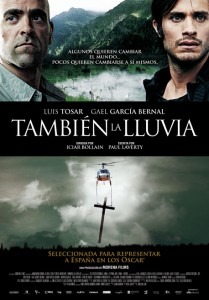

Film También la lluvia (2010)

Like The Motorcycle Diaries and Who is Dayani Cristal?, this is another Gael García Bernal movie that never allows you to forget about its BIG POLITICAL POINT. Casual viewers might find También la lluvia a little heavy handed or didactic, but I think putting the politics front and center can be really important for undergraduates who might never have thought about the relationship between contemporary Latin American politics and the conditions of the conquest.

Like The Motorcycle Diaries and Who is Dayani Cristal?, this is another Gael García Bernal movie that never allows you to forget about its BIG POLITICAL POINT. Casual viewers might find También la lluvia a little heavy handed or didactic, but I think putting the politics front and center can be really important for undergraduates who might never have thought about the relationship between contemporary Latin American politics and the conditions of the conquest.

También la lluvia centers on a film crew that has come to Bolivia to do a greatest-hits reenactment of the early conquest: Christopher Columbus, Bartolome de las Casas, etc. They have chosen Bolivia so that they can find «indian-looking» extras who can speak an indigenous language. It doesn’t matter that the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean would have looked and sounded utterly different from those of the Andes, since their audience in Spain and the US won’t know the difference. Bolivia is also convenient because labor is cheap.

Things start to unravel when it becomes apparent that the actor they’ve chosen to play the film’s indigenous leader is already a leader of a different kind: he’s organizing a protest against the privatization of water service by a US multinational. As the protests intensify, the crew must choose between finishing the film as planned or standing in solidarity with their actors.

In case you missed the parallels between 1492 and today, the film is at pains to make them absolutely explicit. Exhibit A, the tagline: «The Spanish conquered the New World for gold… 500 years later, water is gold. Not much else has changed.» Still, También la lluvia offers a vivid picture of Columbus, las Casas, and other figures who may come across as dry and distant on paper. It also acts as an object lesson for the introduction of decolonial theories that emphasize the continuation of colonial oppression even after nominal decolonization. This film was made to be an educational tool. As instructors, you can help it fulfill its destiny!

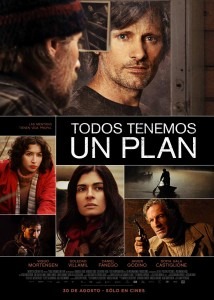

Todos tenemos un plan (2012)

This is the movie I mentioned in my last post in which Viggo Mortensen plays twins with really pronounced Argentinian accents. Viggo Twin A is a successful middle-aged pediatrician whose wife wants them to adopt a kid. This is tremendously inconvenient for Viggo A because it turns out that he kinda hates kids. Viggo Twin B turns up unexpectedly from the Deliverance-style backwater of the Paraná River where he lives with their super creepy childhood «friends» and, kid you not, raises bees. Via *spoiler-y* reasons and methods, Viggo A escapes his ho-hum life by switching places with his twin brother.What could go wrong?

In short order, Viggo A learns it’s much harder than he thought to impersonate someone whose habitus is so utterly unlike his own, even when that person looks exactly like you. Scary, suspenseful, somewhat violent chaos ensues.

Unlike También la lluvia, it’s not immediately clear why this film would be good to teach. But for me this film is intriguing because it deals with some themes that also emerge in South Cone fiction. Firstly, Todos tenemos un plan shows both brothers reading a book by Horacio Quiroga. The Uruguayan author is famous for writing about the rough, male-dominated and violent life in the backwaters of Argentina, and that is precisely the space and ethos evoked 100 years later by Todos tenemos un plan. More exciting for me, however, are the parallels with the work of Argentinian author Juan José Saer, who writes about the same region of Argentina and its relationship to the Paraná River. Saer wrote many novels and short stories about the same group of friends in Santa Fe, including a pair of twins who part ways in the 1970s and go on to lead very different lives. Saer Twin A, like Saer himself, goes on to become a writer in Paris; Saer Twin B stays behind in Argentina and is ultimately disappeared by the military junta. Scenes where Viggo Twin A, in the guise of Twin B, looks longingly at a childhood photograph of the two of them, remind me intensely of scenes in Saer’s work. In short, Todos tenemos un plan would be a great accompaniment to stories about violence and siblinghood in the SouthCone, as well as introducing students to a version of Argentina beyond Buenos Aires.