Gilbert Hernández’s graphic novel “Julio’s Day” (2013) develops a protagonist that is more than the sum of Julio’s actions. In fact, Julio is shown doing very little during his 100 years of life. The graphic novel avoids most of Julio’s intimate moments. In place of a deeply personal story we find a person that is the focal point of a family, community, and national story that lasts a century. Julio’s family lives on the periphery of the 20th century but not because they are a minority family or because they are farmers. I would argue that we all exist at the periphery. In the 20th (and 21st) century there is no individual around whom history turns but instead we have stories. Facebook and Twitter are full of mini-stories that we spend our time checking and re-checking, while the news debates points-of-view on the “most important” stories of the day, and at the same time literature and film create stories that comment on and reflect upon the stories we all live. The story itself is the protagonist of the 20th century and we are all living on its periphery just like Julio.

This story is one of connections, repetitions, change and resistance to change. Hernández’s graphic novel covers 100 years in exactly 100 pages and the content that Hernández chose to include (and exclude) from this story boils Julio’s 100 years of life down to particular events that the author selected as those most pertinent to show. While other critics have said that the story seems scrambled for no good reason, I would not assume that a talented creator such as Hernández would haphazardly put together this text. It should be clear that this story is not a traditional biography and I am convinced it is a story that can only be told in the form of a graphic novel. Throughout the book Julio’s physical presence is not necessary for the text to be able to narrate. Events Julio does not remember or did not see are shown, they are like appendages to his storyline. Only a few short segments of the graphic novel truly inform the one glimpse that we are given into Julio’s internal feelings. Of course, comics can narrate thought with the iconic “thought bubble” but Hernández chooses to omit that as a tool and is forced to show characters’ interior feelings. The graphic novel ends showing Julio’s tears as he sits under a tree where he used to play with a friend that we infer was also his lover. In order to grasp the weight of this scene there are only a handful of segments from the text that we need to recall, and they are all fragments that push the reader to make hypotheses about how to connect these moments with the rest of the graphic novel. The fragments that seem to inform Julio’s final scene show him leaving the house of another man who asks him to stay with him because Julio is the only man who has ever, “been kind” to him. The other segments that fill the other 100 pages of the 100 year story of Julio’s life can then be interpreted in another way – as a larger story of which Julio is a part.

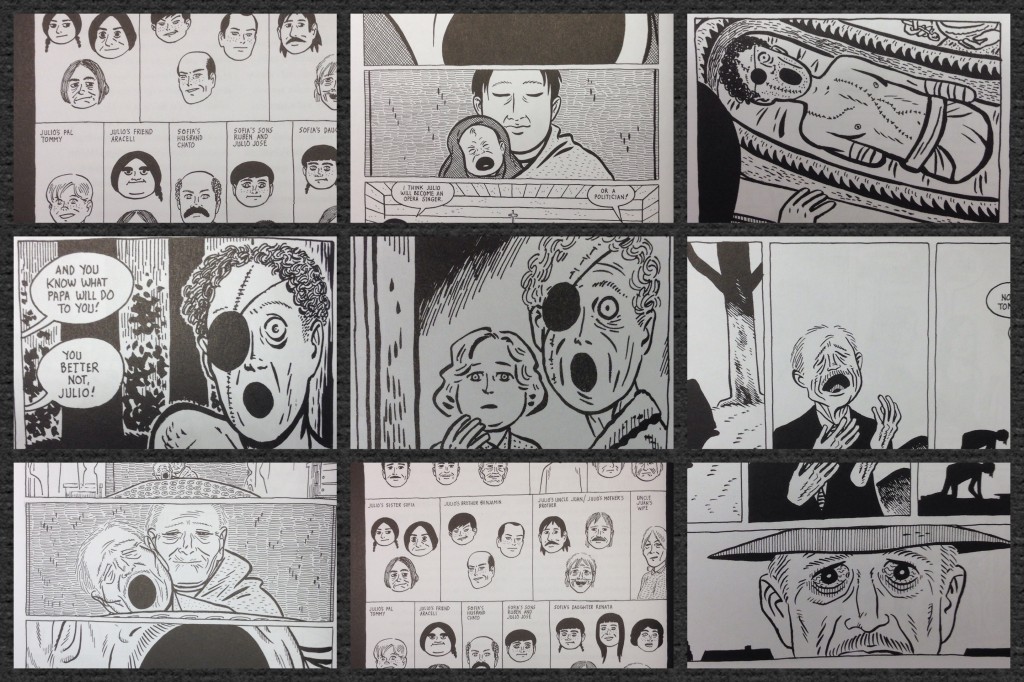

These other segments, which make up the majority of the graphic novel, develop a community connected by Julio, but it is important to notice how the book begins in order to see how this community is to be read. The text does not simply begin with the black panel that is revealed to be Julio’s open mouth. It begins with a visual guide to Julio’s family. It shows the main characters at various stages of life. This visual guide uses Julio as the key to describing familial relationships but it also indicates that being able to identify all of these characters throughout this 100 year story is necessary. This is where the text began to remind me of Cien años de soledad by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The first time I was introduced to Garcia Marquez’s book I saw the Buendía family tree and when I saw the first page of Julio’s Day I was reminded of how GGM’s book is more about the story, the genealogy, than the individual. Where Cien años de soledad is full of repetitions of Aurelianos, in the case of Hernández’s book we have Julios and the appearance of his Uncle Juan. But I think it is obvious that Julio’s life is, indeed, one-hundred years of solitude. He is alone although he is part of this larger story – that is how he is peripheral to the 20th century. Customs have changed, the landscape of his family has changed through death and tragedy (with the exception of his mother), the world has changed but Julio stands at a distance, on the periphery, to be an instrument of measurement against this century of transformation. In the same sense, we watch the stories go by and change happen in the world but we are peripheral to it. Clicking “like” now and again to feel that we are in some way participating.

The story moves along from 1900 to the year 2000 and while Julio has seen the world change he is still resistant to it. His suffering is augmented by the fact that it is now anachronistic, as his great nephew points out to him. It seems to me that rather than see Julio as a character repressing his desires, because we see fragments that suggest that he acted upon his desires to some extent, he can been seen as unable to accept that the world has changed. Julio’s unchanging nature is a signal that he is not the protagonist of this story. Protagonists, in most cases, make decisions, they are dynamic, they grow. Over the 100 years in this story Julio is a constant but he is almost a background character in this graphic novel that bears his name while the climax of the story is fulfilled by Juan Julio and then the denouement shows Julio mourning under a tree and finally the texts jumps to Julio’s death. Julio opens and closes the story but he is more its passenger than protagonist.

The image of Julio’s death, his circular mouth, is an echo of his birth. These images tie the story together neatly in a visual way, but there are a series of these mouths that are all visually similar. The French comic theoretician, Thierry Groensteen, would call these repeated cues “visual braiding.” These images are dispersed throughout the comic but according to Groensteen they can be read as a single thread that runs through the text that can be read independently from it. Hernández’s circular mouths in Julio’s Day appear to be screaming but the artist does not show them producing any intelligible sounds. Even the opening panels of the book show Julio as an infant with a wide-open circular mouth but no traditional comic sound indicators can be found. The family comments that he may grow up to be an opera singer or a politician but these are the only indicators that Julio is actually screaming. This image of the screaming mouth that is unable to communicate its suffering or even utter a word to accompany the gesture can be read as the text’s reaction to the 20th century. It begins and ends with this unintelligible suffering and is punctuated throughout – most notably by the son of the Gomez family – by these horrific gestures. The Gomez family’s son went to fight in World War I, initiating the century in conflict, and returned home as a silent visage of his former self. A reminder of what the century had in store. In the year 2000 Julio’s mouth is left open with this same silent scream.

I believe that this reading of the text can allow another way of viewing what has been called Julio’s repression (even repressed repression). Julio is unable to express, to make intelligible, the suffering of the 20th century and only with the other fragments of lives and events can the story reveal that the world has changed. In a sense the silence of the 20th century ends in the abyss of Julio’s circular mouth at the moment of his death. This fragment is preceded by Juan Julio being able to openly express his love and desire for his partner, something Julio never did (at least that’s the best we can gather from the fragments of his intimate life that Hernández shows).

While all the “big” stories of the 20th century happened Julio lived on their periphery. Being born and dying with the same terrified expression on his face. Julio’s Day shows that an individual, even one that does very little apparently, can communicate the spirit of their time, the zeitgeist, their century. As a counter approach to the opening of my piece I would say that while stories are happening all around us and we seem to be struggling to participate in those larger stories, it is possible to look at the microcosm of a man like Gilbert Hernández’s Julio and see the human side of a century. Telling a story from the periphery of the 20th century is where Hernández is able to find humanity. Julio’s Day is able to condense in a powerful way how a century bears upon an individual, their family, and their life. It tells a story that reminds us that there are humans behind the monumental stories of a century.