In Francisco Goya’s “The Third of May 1808,” a Christ-like figure clad in white holds his hands up in crucified surrender, while the gun barrels and muskets of the French Napoleonic troops hover as disembodied symbols of power. Goya’s painting, with the horror and fear portrayed in the faces of the Spanish troops, is intimate in the affect it evokes in the viewer. It can be interpreted as a political commentary on the hypocrisy of the ideals of the French revolution faced with the reality of the spoils of war.

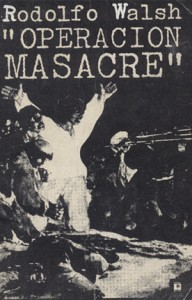

Goya’s painting revolves around light, the luminescent glow emanating from the central figure, a warmth and strength that exceeds what could naturally be expected to shine from the lantern appearing before him. The play of light and dark in the painting, which captures a moment in time before a firing squad ends the life of the central figure, make this painting into a rich referent for Rodolfo Walsh with his Operation Massacre and Roberto Arlt, with his “I Have Seen Dying” or “He visto morir.” Both writers seem to cite the painting, more obviously in Walsh, for whom the first edition of the book bore the image on its dust jacket.

METAPHORS OF LIGHT IN NARRATIONS

Walsh:

The very basis of this book is to shine light on a massacre that at the time Walsh wrote the first edition, had been covered up to the point where very few people were aware it had even happened. Walsh is up against a cover-up, an obfuscation of events, a proverbial pulling the wool over the eyes, by the government. His technique is to light up something that is in the dark.

To do this, he employs a spotlighting technique (this idea was presented by Ana María Amar Sánchez in the seminar “Memorias de Auschwitz” in 2013). Walsh’s narrator never shows the full picture, since the full truth is virtually not available, but rather the narration shines disparate beams of light from one person, to the next, truncating each character’s section with an abrupt cut, as if the lights have suddenly gone out.

We see this in the following examples: the narrator tells the reader about a factual discrepancy saying, “There are no witnesses of what was said. We can only formulate conjectures.” Immediately, the narrative light which had been illuminating that moment in the book extinguishes, while we, as readers find out that in fact no one will ever quite fully understand the situation.

Another spotlight is shone on one of the prisoner’s possible involvement with militant political groups, describing a letter to his girlfriend which ends with the words, “If everything goes well tonight.” The reader is left with the suspicion that the man may have been involved in the militant actions which purportedly justified the government retribution of the firing squad. So as to prevent readers from too much (impossible) certainty in the facts, as if snuffing out a candle light, the narrator ends the section abruptly, presaging, “but everything will go poorly.” Despite wanting to know more information, the reader is left clueless, in the dark about that character’s true status as militant or simply an unfortunate case of being at the wrong place at the wrong time.

We can compare this spotlighting narrative technique, which only shows pieces of a whole, exemplary parts which together spell out a larger picture, to the use of montage in cinema. In montage sequences, significant scenes are portrayed, moments of learning, and change, without seeing the whole progression of change in the characters involved. This has been parodied and has become concreted as a standard trope in any film or TV show representing a growth sequence. From Rocky, The Karate Kid, Clueless and Southpark, I’m sure everyone can think of many examples.

As in a filmic montage, Walsh’s sections jump between characters and action, with momentum building as we get closer and closer to the moment we have been awaiting, when the firing squad opens fire on the prisoners. The narrator explanes, “It’s 9:30 pm. At this moment, thirty kilometers from here, in Campo de Mayo, a group of officials and subofficials are provoking the tragic uprising of June.” While the characters are unwittingly going about their evening routines, the narration jumps to another scene, demonstrating the sort of retrospective construction of facts that a detective must do after gathering evidence. While this narrator does not pretend to know all of the facts, there is a high level of construction that has taken place which derails a linear, uni-spatial narrative, to illustrate the facts to the reader. This sort of editing jump is technically easy in film and viewers are accustomed to it. However in a work of non-fiction, as this work is, this technique introduces a plurality of voices, testimony and narrative construction, which makes having a single, concretely represented truth virtually impossible. It is an array of parts, or spotlights, which shine light on facts in their piecemeal way.

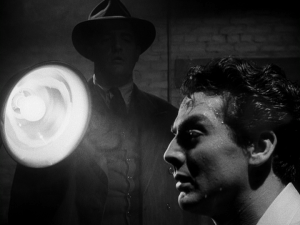

Walsh’s use of abrupt and disjointed spotlighting as a narrative device can be read as a subversive reversal of disciplinary light. My conception of disciplinary light comes from popular tropes in cinema, specifically the overhead hanging light contrasted with a dark room, used by detectives or officers during interrogations with suspects. This light, which swings on a cord and can be strategically directed into the face of the suspect, is a menacing light that represents authority and discipline. Another image of disciplinary light is the scanning floodlight in a prison yard, from which escaping prisoners must hide as it passes by. By employing a spotlighting narrative technique, Walsh challenges authoritative uses of light, which are used even during the execution of the prisoners by firing squad, the very event that his work aims to bring to popular consciousness, or to “bring to light.” At the moment of narration of the killing, in a section entitled “The killing”, the narrator says that, “The prisoners seem to float in a vivid lake of light.” The blinding light, which emanates from the police transport vans, is what permits aim by the firing squad. However, a handful of prisoners disappear out of the glare and into the darkness, escaping their imminent deaths. Returning to Walsh’s use of the spotlight as a narrative metaphor, it presents itself almost as a challenge to the authorities who themselves use light in disciplinary ways.

Arlt:

Arlt’s use of light and color is like that of Goya – dripping with heat and vibrancy, which in Arlt’s chronicle, radiates through the narration. Describing the political prisoner who will be executed by firing squad, the narrator recounts, “It’s Severino Di Giovanni. Prominent chin…Thin lips, extraordinarily red. Red forehead. Red cheeks. Eyes blackened by the effects of the light… The lips like glossed wounds. They part slowly and the tongue, redder than a hot pepper, licks them, dampening them. This body is burning with heat. Relishing death.”

Arlt’s primary approach to the firing squad is through a photographic narrative technique. The initial scene is set with a sequence of establishing shots, under the section title, “Litany.” The narrator describes the scene, “Space with blue sky. Cobblestone paved. Green field. Something like a living room chair in the middle of the field. Troops… Lamps whose light punishes darkness.” The description of the physical space where the execution will take place is not a traditional narrative that enters a new space, observes and builds the appearance for the reader in sweeping sentences similar to the way our sweeping gaze scans a room upon entering. Instead the disparate observations stand alone, as if perceived through a photographic lens, snapshots capturing varied images with the turn of the lens to focus on each individual element.

As readers, we are captivated by the thick description, and become drawn in, hypnotized by the coming moment of death. As the prisoner takes his final steps toward the chair, his trajectory is more of a waddle, as his feet are bound by the rope. The narrator says that some of the spectators begin to laugh. The narrator offers explanations as to why they could be laughing at such a moment, suggesting, “nervousness?” then shrugs off the question with a “Who knows!” What seems like an earnest question of why people are laughing, by the end of the article fits into a critical framework that the narrator constructs, criticizing the entertainment-value of spectatorship of the event. It becomes a spectacle which gives pleasure to the spectators. Borrowing from Blumenberg’s metaphor of shipwreck which is entertainingly observed from shore, the spectators here are at a distance safe enough away to be able to laugh.

The last section of the chronicle, entitled “Death” describes the post-execution exit of journalist spectators who have come dressed in dancing shoes to the execution. The narrator suggests that the entry to the penitentiary have a sign that reads, “Laughter is prohibited. Dance shoes are not permitted inside.” This is a scathing critique toward society, who are not only the spectators, but who, in taking fascinated pleasure in the execution, collaborate with the juridical powers that discipline Di Giovanni, an anarchist, with the sentence of death.

The photographic narrative style that Arlt chooses to employ stands as an aesthetic choice, but also has critical significance in the allusion to the way photographs create a spectacle of various sorts. If in the article Arlt describes the spectator public, seeing and expecting to take pleasure in the execution, he embodies that critique through his narrative style. By making his words into photographic images that transform the reader into the spectator, the reader becomes no better than the spectators actually present at the execution. There is a wider message that it is not only the judge who condemns Di Giovanni, but all of society is complicit, and even worse takes pleasure in his death.

In Walsh and in Arlt light is used as a metaphorical tool for narration. In Walsh, a partial illumination like a spotlight, and in Arlt, like flashes to accompany brief photographic images, that compile to make a spectacle of death. As Goya’s painting stands as a political critique of the hypocrisy of French revolutionary ideals, in both Walsh and Arlt, there is a political commentary and aim. In Arlt, the scathing critique toward a spectator society is evident. In Walsh, as he writes in the prologue to the book, his aim is to raise consciousness as to the deadly, extra-judicial practices of the military-led government. These events, from 1956, happened a full twenty years prior to the official start of what we know of as the most recent argentine military dictatorship. Walsh had false papers and was living clandestinely in the 1970s when his home was bombarded and he was disappeared by the government. The cult of Walsh is thriving today in Argentina and this work is fundamental to that memory.

(This work was originally presented at the GRACLS Conference at the University of Texas at Austin on October 11, 2013)

WORKS CITED:

Arlt, Roberto. «He visto morir.» Las aguafuertes porteñas de Roberto Arlt: Publicadas en «El Mundo,» 1928-1933. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Culturales Argentinas, 1981. 193-196.

Blumenberg, Hans. “Light as a Metaphor for Truth: At the Preliminary Stage of Philosophical Concept Formation.” Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision. Ed. David Michael Levin. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, 1993: 30-86.

Walsh, Rodolfo. Operación masacre. 39th ed. Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Flor, 1972.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Lauren S. Gaskill is a doctoral student in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of California, Irvine. She researches contemporary Latin American literature under the guidance of Dr. Ana María Amar Sánchez. Lauren earned her bachelor’s degree at Georgetown University with a major in Spanish and a minor in Portuguese.

CITE THIS ARTICLE:

Gaskill, Lauren S. «Narrating the Firing Squad: Metaphors of Light in Textual and Visual Representations.» Pterodáctilo. Revista Pterodáctilo, 11 Dec. 2013. Web. [Date article accessed]