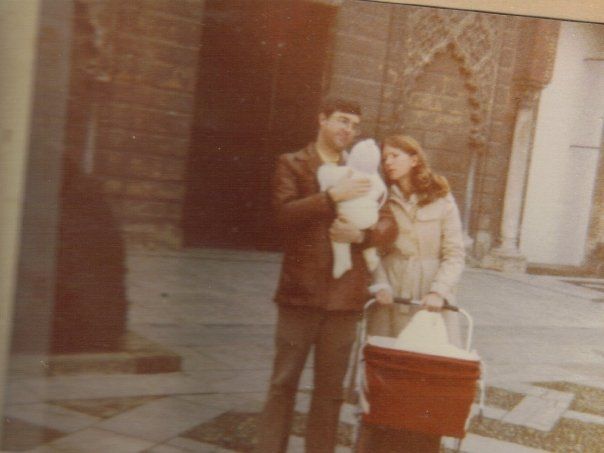

My parents married in 1977. Shortly after that, my dad, a naval officer in the JAG Corps, got sent to the base in Rota, in southern Spain, where my parents stayed until 1981. For part of that time they lived in base housing, but when I was born in 1979 they were living in a rent house in Puerto de Santa María, close enough to the Bay of Cádiz that old women in black would dig snails out of their lawn to later poach in butter and garlic.

I love looking at pictures of my parents from those days because, as Daniel Mendelsohn asks, “Who, after all, can resist the fantasy of seeing what your parents were like before you were born, or when you were still little—too little to understand what the deal was with them, something we can only do now, in hindsight?”

It wouldn’t be correct to say that their time in Spain was the most interesting period of my parents’ lives. They met and dated in D.C., and later moved to Virginia, and then Charleston, and then to Fort Worth, Texas. They divorced in 1997 and each remarried, expanding my family in ways that I treasure. In her last years, Mom owned horses and led a nursing school, and Dad has traveled places far more exotic than Spain with my stepmother.

But I’ve always looked at Spain as holding the secret to my family and, therefore, to myself. This idea spurred me to work harder in my high school Spanish classes, to major in Spanish in college and, eventually, to study in Madrid before my senior year. And I know that Spain loomed large for my parents, too. It’s still a source of dinner table stories for my dad. And in a corner of the kitchen of my mom’s last house in Tulsa, she kept her Spanish cookbooks lined up next to a small bottle of saffron we brought her from Madrid, and a large bottle of brandy we brought my stepfather, and a couple of olive jars that she brought home from Spain in 1981.

…

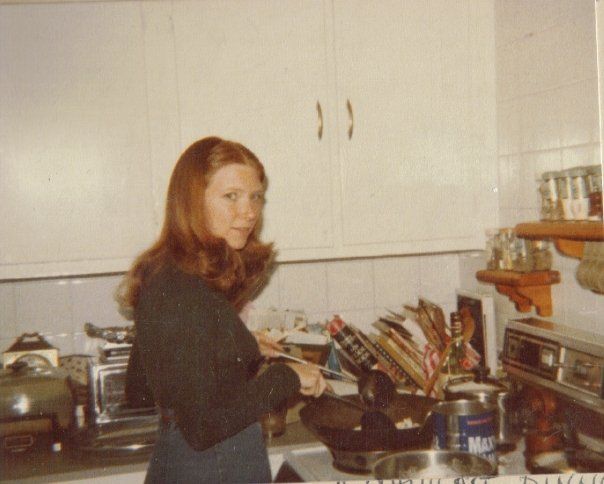

My mom didn’t learn to cook Spanish food in Spain. She ate in Spain, and she cooked in Spain, but the food she made there was homesick food, Americanized versions of Mexican and Chinese food, and the Southern food she ate growing up in Atlanta.

But after being back in the US for a while, she got homesick for Spanish food. And so she learned to cook Spanish food so well that, by the end of her life, one of her two go-to specialties for important occasions was a comprehensive spread of Spanish tapas. The other was lobster, which was what she made when she didn’t want a fuss.

When she made Spanish food, she wanted a fuss. She would scour the grocery stores of Charleston, Fort Worth, Tulsa—wherever she was living at the time—for suitable ingredients; she would worry over every bit of her own work and, if she delegated a task to a family member, say chopping potatoes for the tortilla española, she would fret annoyingly over his shoulder.

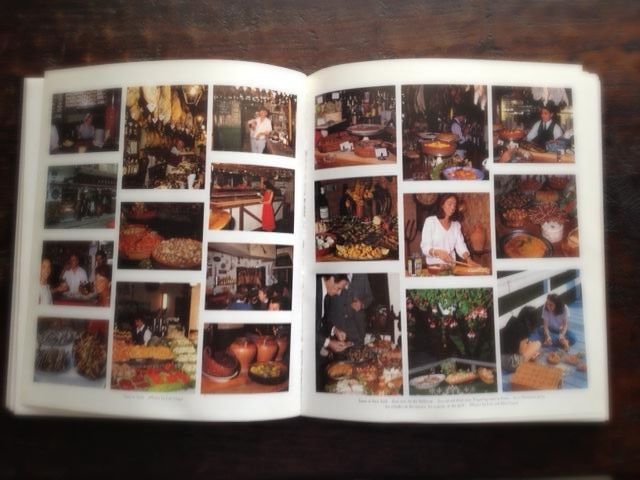

Most of her recipes came from two books by Penelope Casas, The Foods and Wines of Spain (1982) and Tapas: The Little Dishes of Spain (1985). Casas, who passed away this week at the age of 70, wasn’t Spanish, but then neither were my mom and dad. She was from Queens, a Spanish teacher, a writer of letters-to-the-editor on subjects involving Spain and Spanish food, who willed herself into becoming the foremost American expert on the country’s cuisine. The Spanish government gave her its National Gastronomy Prize in 1983; the New York Times called her “an authority on the foods of Spain” in its obituary.

The Times obit tells just how she made that leap: Casas wrote a letter challenging Times food editor Craig Claiborne on his spelling of a Spanish dish; Claiborne, impressed, asked her to make him a Spanish meal. After tasting it, he called his literary agent to get Casas a book deal.

But just as interesting to me is the story of how Casas, a Greek-American daughter of an optometrist, ended up in Spain’s thrall in the first place. The Times writes:

Her fate as a Spainophile was sealed, her daughter said, during a semester abroad in Madrid in the early 1960s, when she met her future husband, Dr. Luis Casas, who would collaborate on several of her books.

At the time, though, he was a medical student, and the son of her student-exchange host mother.

The young couple spent a lot of time tapas bar hopping. In a 1979 interview, Mrs. Casas told Mr. Claiborne, ‘We rarely got home before 5 in the morning, and then got up to make an 8 o’clock class.’

So, not much different from my parents—just an American who found herself in Spain at a critical moment in her life, and who let the country become a defining fact of her existence.

…

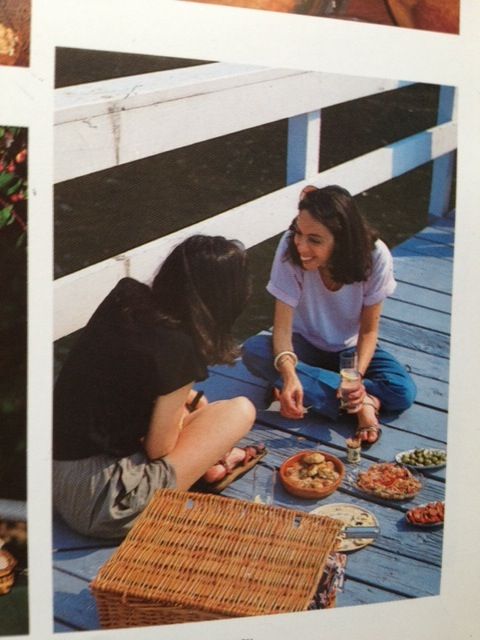

Not much different from me, in fact. There’s a recipe on page 166 of Tapas that, as far as I know, my parents never made. It’s for mejillones gayango, mussels stuffed and fried the way Casas says she had them at the now defunct Bar Gayango. To make them, you mince the mussel meat and mix it with jamón serrano, manchego, garlic, onion, and parsley, then spoon that mixture back into the half-shell, bread the whole thing and fry it. The recipe is the closest my wife and I found for the mejillones we had at a different bar, this one in San Sebastián. We went there one night the summer I was twenty—Hannah had come with a friend to visit me as my school term in Madrid was finishing up.

The three of us traveled around the country, ending up in San Sebastián, a city that, again as far as I know, my parents never visited. We were drinking rum and cokes, and we kept ordering them, as much for the stuffed mussels that came with our drinks as for the drinks themselves. When we finally couldn’t drink anymore the mussels kept coming because the bartender had an eye for Hannah’s friend.

Back in the States that following school year, we made the mejillones when Hannah and her classmates organized a progressive dinner party, the kind where you go from apartment to apartment, eating a different dish at each place. It was the sort of party that young people plan when they want to feel like adults—the kind of thing I can imagine my parents participating in a few decades ago. In fact, Casas’ book seems pitched right at our nervous, barely grownup demographic. In Tapas, for example, she writes: “Now, thanks to tapas, the yawning gap between cocktail and dinner parties has been bridged, creating a relaxed, free-flowing atmosphere in which the desire for a tidbit to accompany a drink merges successfully with the need for a well-balanced meal.”

It’s remarkable that a cookbook could serve the same role for two generations. In a recent blog post (the one where I saw that Daniel Mendelsohn quote above), Corey Robin writes:

Do we not, all of us, have to come to terms with the mystery of our parents, to acknowledge that their inner life is neither exhausted nor consumed by the life we know, by the care and devotion they bestow or don’t bestow on us? That their real life may be the life they lead elsewhere, which may also be on a page, whether a diary, a letter, a legal brief, a memo? Are not all of our parents mysterious writers, composing their poems behind closed doors? Do we not have to bestow that independence upon them if we are to have our own?

That’s the trick, isn’t it? Understanding the poems that are our parents’ lives while finding the language to write our own? In her books, Penelope Casas provided that language, the means through which my parents explained themselves, through which I approached them and, years later, through which my wife and I started to explain our life together. Casas will rightly be remembered as an ambassador for Spain, a Spanish teacher writ large, but for our family she was something more.