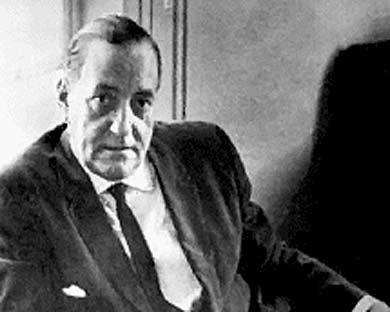

Dig the French accent on Cuban author Alejo Carpentier in the video below:

Why do I bring this up? In a very sharp essay in the new issue of Pterodáctilo, my colleague Hannah Alpert-Abrams argues that the North American publishers and translators of Alejo Carpentier’s Los pasos perdidos (The Lost Steps, 1956) downplayed the Latin American nature of the novel to make it more palatable to US audiences. Instead, she says, they turned it into a novel about an encounter with the Other, when, she writes, “The narrator is Latin American in origin; the question posed by the novel is whether this man, altered by his encounter with Europe and North America, can ever truly return to his place of origin.”

She’s right, but it’s a kind of funny theme given the questions that surrounded Carpentier (during his life and after) about his own authority to speak for Latin America. Gonzalo Celorio, for example, complains that, for most of his career, Carpentier’s view of Latin America was the view of an “outsider,” and one that looked on Latin America as an exotic Other.

Carpentier’s father was French and his mother Russian; he always insisted he was born in Cuba, but now we know that he was actually born in Switzerland. There’s something fascinating about that insistence, and about his constant theorizing on Cuban (and Latin American) identity. Carpentier, after all, is the guy who wrote that expressing a national identity “de esencias” comes from “using one’s most spontaneous language, listening to that which sings in the most intimate of one’s being.” But he also traded in on the cache of his French language skills, and he lived for most of his adult life outside of Cuba.

What’s more, he saw Cuban culture as inherently built around foreign elements—except when he was promoting some «authentic» and «pure» forms of Cuban culture (like the son) over ones he saw as impure (like the danzón). Carpentier’s notions of nationality and origin were full of tensions and contradictions. Sometimes, as in the video above, he seems conscious of that. But sometimes he doesn’t, and that’s what makes studying him both frustrating and rewarding. He’s like a guy walking around in a maze, only sometimes he forgets he’s walking in that maze. Tracking his movements, and trying to figure out the reasoning behind his movements, can be exceedingly difficult.