The place for Afro-Latin@ poets in the literary curriculum has been scattered and disguised, sometimes even mixed with Black Studies, Latin@ Studies or African and African-Diaspora Studies, but has rarely had its own soil to flourish in. The blurb from Booklist on the cover of the anthology says:»¡Manteca!, like its English translation, ‘butter,’ will melt delectably in the mind, creating flavors and nuances to ponder again and again». But aside from butter, or the correct translation, lard, ¡Manteca! refers to the song by the same name composed in 1947 by jazz musicians Dizzy Gillepse, Chano Pozo and Gil Fuller. As anthologist Melissa Castillo-Garsow says this piece “is one of the foundations of Afro-Cuban jazz […] Not only as a symbol of the significance of African-American and Latin@ collaborations, but the beginnings of what can be thought of as a distinct Afro-Latin@ sound in the United States that can be traced through boogaloo to salsa to hip hop” (xix). ¡Manteca!, as its jazz counterpart, opens a space of negotiation. It opens a space for collaboration through rhythm and sound, in which the poets and their voices enter in the dynamics of the rhythm: of going back and forth, and improvising in the moment.

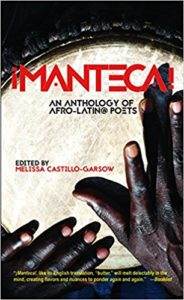

Because literature implies a reaction to our realities and sensibilities, it is clear then that there must exist a space in which the specificity and sensibility particular to the Afro-Latin@ experiences can be read as such. With the anthology ¡Manteca! An Anthology of Afro-Latin@ Poets, Melissa Castillo-Garsow creates a space in which voices of self-identified Afro-Latin@ poets can grow in a process of negotiation. This anthology will help scholars in the fields of Latin@ Studies, Black Studies, African and African Diaspora Studies, and scholars in the blooming field of Afro-Latin@ Studies.

The anthology compiles the voices of forty self-identified Afro-Latin@ poets, twenty men and twenty women, and recognizes “not collaboration but people, those Latin@s who ‘couldn’t shake their skin,’ or their Latinidad” (xi). In the introduction Castillo-Garsow shares what she told writers for the compilation process: “Just send me your best work, the work you feel represents you best as a poet, present and/or past, if you’re so inclined” (xxxiv). This translates into a variety of reading experiences that respond to the interests of each reader.

The anthology, unlike other poetry collections, is not divided into themes, or regions. Rather, each poet has his or her own section, allowing the reader to create dialogues amongst the different poetic voices. However, the reader will find shared points of departure. One of these points is the negotiation of an identity, as in Miguel Algarín’s “Ray Barreto: December 4,1976”or “A salsa ballet: Angelitos Negros” where we find the dynamics of a jam session which is about “listening, shifting, and transforming”; or as in Peggy Robles-Alvarado’s “¡Bomba!”, pursuing the own dynamics of exchange in bomba music, but also in terms of self-identification: “No nací en Puerto Rico pero nací con este ritmo encarnado en mi ser”(54). Similar to this is the negotiation found in Tato Laviera’s poems, where the barrio as a space of exchange and compromise. It is not only what shapes you, but what shows the failure of the “American Dream”. His poem “Lady Liberty” shows the fracture of the dream, the evidence of an illusion, as lady liberty stands decayed and discolored.

Another shared departure are the rhythms of the African diaspora found in Algarín’s and Robles-Alvarado’s works. These poems show an internal structure that moves following a certain rhythm. It is this rhythm in which the voices move between English and Spanish. It is also the thing that makes it difficult to point to a certain category and that also alludes to those instruments of the diaspora which entails them to those rhythms: the congas, the plena, the bomba, and that action of negotiation in music often found in African diasporic music.

As an anthology of self-identifying Latino of African descent, memory has an important role in weaving together these poetic voices. However, it is a memory triggered by the senses which gives another twist to the title of the anthology, the lard as that which trains our palates from a young age. In Gustavo Adolfo Aybar’s “Morir Soñando”, memory is the retelling of the recipe, remembering and tasting from that memory. In Marianela Medrano’s “Jamón y queso” the relation to memory is the act of reviving the taste of what her dad used to eat, the closeness of the nothingness of that memory. Memory in these poems is what allows these subjects to create their realities and keep the culture alive, while at the same time reformulating them. Memory guides the poets in the anthology to a final shared space, language.

Language is what constitutes poetry, and what constitutes us as subjects. Spanish for some of these poets serves as an anchor, but also switching between English and Spanish allows them to navigate the space. As Tato Laviera says, what characterizes him is “a blackness in Spanish, a blackness in English” it’s the instability and the arbitrariness of the tongue (180).

In sum, ¡Manteca! An Anthology of Afro-Latin@ Poets it’s a well thought out compilation of amazing poetic voices. It provides a space much needed for Afro-Latin@ poets, as it allows these voices to collaborate not just as poets, but also as people who share experiences through the color of their skin. This pioneer anthology raises awareness of the need of more literary works that take into account and claim the experiences of Afro-Latinidad.

Title: ¡Manteca! An Anthology of Afro-Latin@ Poets

Editor: Melissa Castillo-Garsow

Publisher: Arte Público Press

Release Date: July 2017

Pages: 415