Overview

This semester I’ve been taking a course cross-listed between Architecture and Latin American Studies called “Architectures of Migration: The Space of Texas Detention Centers.”

This is a revolutionary multimedia and multi-disciplinary class that examines incarceration in different contexts. Led by the Humanities Action Lab at the New School, we collaborate with 19 other universities nation-wide. Our work will culminate in a traveling national exhibit that will showcase issues of incarceration and detention through photographs, graphs, and a host of online multi-media. The University of Texas branch of this project is the only group focused on the physical space of migrant detention centers and how this contributes to the criminalization of migration.

Texas serves as a migration gateway and houses 33 detention centers that hold men, women, and children fleeing to the U.S. from all over the world. As migration to Europe and the U.S. fills the news, issues of xenophobia, access, space and citizenship are at our backdoor.

Since beginning this course, several things have been incredibly striking: the privatization not just of incarceration but of detention and its amplification during the Obama administration, the power of grassroots movements and activism to make changes, and the heartbreaking variety of stories of migrants and asylum seekers who have been criminalized and put in detention. These issues have been apparent in the activities I’ve been involved in with the class – mapping exercises with ex-detainees and interviews with migrants in detention centers.

Cognitive Mapping

I’ve been performing “cognitive mapping” exercises with ex-detainees at a local shelter that houses migrants and refugees seeking asylum called Casa Marianella. Located in East Austin, Casa is one of the very few alternatives to detention – offering migrants a place to stay along with English and career help to get them started in the United States.

The term “Cognitive Map” can refer to both representations of spatial knowledge as well as mental (neural) structural and processes. For this course we have been thinking of cognitive mapping as relatively structured representations of the environment that document individual people’s cognitive spatial schemes for understanding their physical surroundings. They can be drawn as diagrams, or “maps,” showing the distribution of places and locations across a 2-dimensional surface, and usually indicating relationships between them.

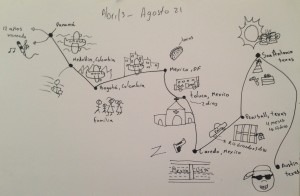

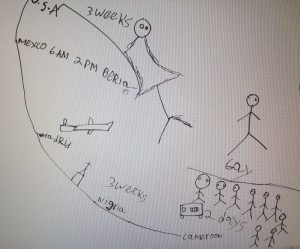

In our cognitive mapping exercises with Casa Marianella we have asked participants to represent their journey, marking each leg by a point and then essentially connecting the dots. We encouraged participants to represent the different parts of their journey with symbols or words that encapsulated some aspect of their time in that space.

After mapping their journey, several participants were asked to map the actual space of detention and drew renditions of their rooms in detention and other aspects that represented these spaces for them.

Although some participants are understandably more comfortable with the idea of representing themselves visually, each map helps tell the complicated global story of where these people came from, why they left, and the moment their journey was paused as they were detained. Below are a few of the many stories of formerly detained migrants who were offered shelter at Casa Marianella.

Individual Mapping Stories

Miguel:

Miguel is from Bogatá, Colombia where he was a successful reggaetón singer. He fled Columbia after guerrillas began persecuting his father and himself threatening kidnapping and extortion. Miguel spent time in Panamá where eventually the guerrillas followed him, causing him to flee further North. Miguel came to Mexico where he went to cross the border to the U.S. at Laredo. When he arrived at the bus station, the Zetas gang was waiting asking for codes to make sure all those attempting to cross had used a coyote or smuggler. When Miguel didn’t know the code, the Zetas attempted to kidnap him and he narrowly escaped, running to a taxi that brought him across the border. When the U.S. border patrol went to Mexico to verify Miguel’s story they found the taxi driver that had given him passage was killed by the Zetas. After spending several days in detention in Rio Grande, Miguel was put in detention at Pearsall where he stayed for four and a half months until he won his asylum case and was released. Miguel has since gone to Colorado to join one of his best friends from Colombia and begin work in construction.

Elvis:

Elvis is originally from Bastos, a city in Cameroon. In Cameroon, Elvis described not being accepted into society because of his sexual orientation. He was persecuted and had to flee for his life to Nigeria. In Nigeria, Elvis spent 3 weeks where he came into contact with a church group and pastor who offered to help get him out of Africa in order to seek asylum. He flew to Madrid as part of the crew of a church group and then was offered passage to Mexico. Elvis never expected to find himself in the United States, but crossed the border seeking asylum and was placed in detention for three weeks. His case is still on-going and he is currently residing at Casa Marianella in Austin.

Some Conclusions

Listening to these stories has highlighted the importance of putting a human face on immigration and publicizing the criminalization of migrants. In talking to migrants who have experienced detention the physical space, materials, and lack of resources greatly increases the effect of criminalization in their lived experience. When people I interviewed represented their experience through mapping and drawing, it helped them to talk about, contextualize, and physically represent their story and touch on some of the trauma they’ve gone through. As most detention centers in Texas are privately owned, gathering information is complicated and part of the idea of this class is simply to call attention to what is going on.