“By public executions I mean all penalties meted out in a public place. Execution originally meant the carrying out of any sentence, not only death sentences.” – Pieter Spierenburg, The Spectacle of Suffering

“The historical illegality of gender trespassing and of queerness have taught many trans/queer folks that their lives will be intimately bound with the legal system.” – Eric A. Stanley, Captive Genders

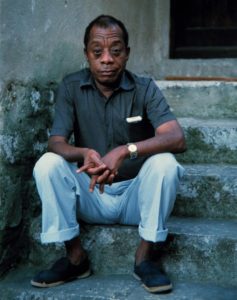

Upon a cursory gloss there does not seem to be much that ties James Baldwin to the Caribbean. However, upon closer inspection the author’s presence and awareness of the region becomes evident. In the Baldwin biopic I Am Not Your Negro, by Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck, viewers learn that the moment Baldwin learned of the murder of his friend Medgar Evers via radio broadcast he was in Puerto Rico. During his visit to the island he wrote his second play Blues for Mister Charlie, collaborated with photographer Richard Avedon on a project entitled Nothing Personal, and celebrated his birthday with his brothers, sisters, and mother who flew out for a week to join him. A decade after his visit to the island Baldwin would later publish If Beale Street Could Talk, a novel featuring a protagonist who is falsely accused of rape by a Puerto Rican woman. In addition to his tourism and fictionalization of Puerto Rico, Baldwin was also sympathetic to the Cuban Revolution. According to his publicly released FBI files: “The April 6, 1960, edition of The New York Times contained an advertisement by the Fair Play for Cuba Committee and Baldwin was one of the sponsors.” The FPCC was an activist group that opposed the US embargo of Cuba, and the FBI called it a “pro-Castro propaganda organization.” It is clear the Harlem-born author’s connection to the Hispanic Caribbean amounted to more than a tourist visit.

Bilingual readers of queer literature en español acquainted with James Baldwin are likely to also know of the acclaimed Cuban novelist Reinaldo Arenas. Those who have read the book or seen the film adaptation of Arenas’s Antes que anochezca are well aware of the homophobic violence that was secretly perpetuated along with Fidel Castro’s anti-imperialist politics. To many black public intellectuals of the United States in the 60s and 70s, however, the Cuban revolution served as “a discursive site for debating the tactics and ideology of black freedom” (Chiyoki Iked). Testimonies such as those penned by Reinaldo Arenas, which recount the terrors of dictatorship, were to make clear to everybody paying attention the high price of revolution. While one can only speculate what Baldwin’s position on the Cuban Revolution would have been had he lived to see the Special Period or to read Antes que Anochezca, one thing is certain: the two authors share many commonalities. In addition to both being gay men, Reinaldo Arenas and James Baldwin were both high profile writers subjected to unrestrained state surveillance who each wrote autobiographical carceral narratives.

As a light rain drizzled the streets of Paris during the evening of December 19th, 1949, at age twenty-five, James Baldwin was arrested and imprisoned during his first year in France. While it was brief stint, the young writer’s humiliating imprisonment, a ludicrously excessive punishment for such a petty offense, offers an account of carceral alienation that reveals the transnational scope of inescapable power hierarchies indifferent to socially marginalized lives. Baldwin’s brief 1955 essay Equal in Paris recounts his detention in what he dubs: “l’affaire du drap de lit.” His crime: being in possession of stolen bed linen. While his own mother told him that if this was the worst thing that ever happened to him, he could consider himself “among the luckiest people ever to be born,” and he himself recounts the incident as the perfect “comic-opera,” I would caution readers of taking the author’s belittlement at face value. Upon confronting the apprehension that pervades the essay there is no doubt that Baldwin’s prolonged subjection to French police custody is clearly traumatizing. His carceral narrative describes a realization of what his close family friend and biographer David Leeming has called “the precariousness of his expatriation.”

Equal in Paris concludes as Baldwin, after having his court date rescheduled, is finally escorted to be trialed at the palais de justice and learns that his case has been dismissed. When the courtroom hears the retelling of“l’affaire du drap de lit,” the story causes a great merriment to all in attendance. The laughter sends chills through Baldwin, who recognizes it as “laughter of those who consider themselves to be at a safe remove from all the wretched, for whom the pain of the living is not real.” In this comic situation the insidious laughter indicates an indifference to Baldwin’s well being, and in turn a disregard for black life. In one of his last publications made before dying of cancer at the age of sixty-seven, The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985), Baldwin elaborates on the feigned “objectivity” within courtroom dynamics: “Each of us knows, though we do not like this knowledge, that a courtroom is a visceral Roman circus. No one involved in this contest is, or can be, impartial.” By alluding to the theatricality of courtroom proceedings Baldwin aligns himself with other incarcerated queer writers who have attested to the perfunctory and prejudiced nature of sentencing and execution processes.

It is without question that both authors were subject to distinct kinds of imprisonment, and it may seem almost laughable to compare Baldwin’s week in prison to the several years Arenas spent behind bars. Yet through their entanglement with the legal system they each became critical of how penalties were performed in public. In Antes que anochezca, Reinaldo Arenas describes the revolutionary tribunals of the Castro regime–in which “los juicios eran representaciones teatrales donde la gente se divertía viendo como condenaban al paredón a un pobre diablo”–as spectacles of punishment only amusing to those in power and their supporters. While the optics of abusive prosecution may be humorous to those at a safe distance, for those who endure, what Erica R. Meiners calls, «targeted criminalization» it is no laughing matter. What these two parallel scenes of public execution by Arenas and Baldwin illustrate is that, as a racialized and/or criminalized subjects, the social ritual of appearing before a tribunal can become a type of violence in and of itself.

Sources:

Arenas, Reinaldo. Antes Que Anochezca, 1992.

Baldwin, James. Equal in Paris, 1955.

–-. Evidence of Things Not Seen, 1985.

FBI. “James Baldwin Part 01 of 02 PDF.” vault.fbi.gov.

Ikeda, James Chiyoki. “Black is a Country”: The Impact of the Cuban Revolution on American Black Radical Solidarities, 2017.

Leeming, David. James Baldwin: A Biography, 2015.

Meiners, Erica R. For the Children? Protecting Innocence in a Carceral State, 2016.

I am Not Your Negro. Dir. Raoul Peck. 2016.

Spierenburg, Pieter. “Preface.” The Spectacle of Suffering, 1984.

Stanley, Eric A. “Introduction.” Captive Genders, 2011.