I’ve spent the last month living in Rio, taking a course on the African diaspora through UT’s department of African Studies. We’ve been staying in Copacabana, in the wealthy, heavily touristed Zona Sul of Rio. If you walk to the very end of Copa, into a neighborhood called Leme and take a small, graffitied stairway up a hill, you arrive in the community of Chapeu Mangueira, one of the first favelas to be pacified by the UPP (Pacifying Police Unit) and an area actively working towards becoming «eco-friendly.» The sandwiching of this community between the pavement (asfalto) of Copacabana and the manicured trails above the favela creates a striking juxtaposition.

I met some community leaders a couple of weeks ago who invited me to come along for a hike in celebration of Brazilian Earth day. I arrived in front of the associação dos moradores (community association) where there was a crowd of wealthy, white Brazilians from the Friends of Copacabana neighborhood association who were ready with their walking sticks, hats and bright-green t-shirts.

The guides who led the tour were part of the community association who had received a government grant to re-forest the land. Initial reforestation efforts proved successful; after the grant ran out, the association caught a break when the RioSul shopping center built their mall two stories higher than law allowed. In a typical Brazilian political maneuver or jetinho, they evaded having to tear it down by funding a preservation initiative and pushing to have the natural area above the favela turned into a national park and trail for tourists. It has recently been deemed a natural cultural heritage site by UNESCO.

As we wound through the favela, gaining spectacular views of the surrounding bay and cityscape, the roads turned from paved to dirt and cement buildings became brick and stick shacks. As the last buildings disappeared, and we trekked through heavily treed trails, we reached the summit where the leader of the hike (not the community organization) told us that we should check out the shopping center on our way down as we could feel good about our purchases since they helped create this preserved area of land.

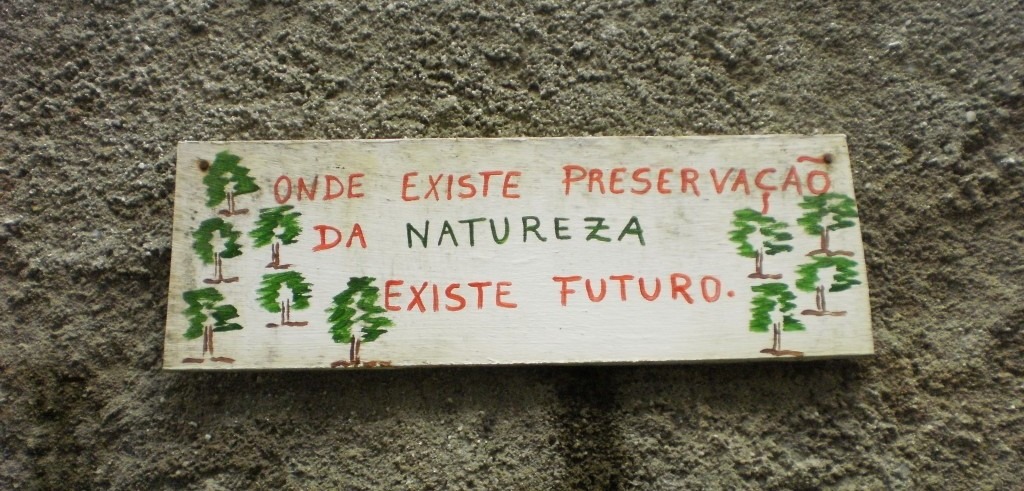

Reflective of the stark inequality at work in Brazil (the catalyst for the protests last summer), this community was only offered the basic services citizens should be entitled to because a shopping mall was built near where they lived and they have a good view. Although organizations like the associação dos moradores work to bring environmental education into the favela, they are dependent upon funding from a mall where their residents are not welcome and can hardly dream of affording. While the trails above the favela were clean and well-maintained, the favela itself had trash strewn in every corner. So who are these preservation initiatives for? The tourist looking for a good view? In a marginalized area, how can environmental consciousness and education interact with tourism to create real sustainability — a community that has rights to their land, access to basic services, autonomy, and recognition as more than part of the landscape on the way to a better view?