I. What is paleography?

The ability to read and study ancient or historical handwriting styles that are no longer recognizable and familiar to modern readers is called paleography. Those of us who want to work with primary sources that have not been transcribed by historians and other diligent scholars must learn this skill, whether the writing is from the 1960s, the 1850s, or the 1300s.

I first wrote a short piece on paleography in the spring of 2016, as part of a collaborative series on this discipline. At the time, I was new to paleography, and most of my successes and failures stemmed from my firsthand experiences, much embarrassment, and many hours struggling with early modern Spanish texts. What struck me the most was that accessing an archive does not always mean that I will be able to actually read the texts that I proposed to read.

After being aware of a few different alphabets that writers could use in their shorthand, the next most important thing is to study how languages can sound.

II. Good Paleographic Practices (Continued): Losing (or winning) the phonemic lottery

Modern spelling has been standardized through systematic institutions like the Oxford English Dictionary and the Real Academia Española, and we spend many years in school learning what the “correct” spelling is for our mother language. This is not always the case with early writing, even in texts from the 1800s.

Instead, medieval and early modern writers in particular wrote based on how words sounded to them. In linguistics, this means that they spelled words based on the phonemes (letter sounds) that they could hear. If they spoke in a dialect or a “non-standard” version of a language, their spelling would reflect that. Usually, scholars that speak more than one language have an easier time with the problem of phonemes in writing, as they have been sensitized toward multiple languages and their sound variations, or the “allophones of phonemes.” This means that a “letter” in a language can actually have multiple sounds (usually sounds that a native speaker does not notice, but that exist), which means that a word could actually be spelled in a few different ways depending on the author’s perception.

In the case of Spanish—what I work with—scholars agree that as a language the spelling variations are not completely unpredictable. But what does that mean? Here are a few examples for how the verb “hubieran” from haber could be written in early texts, based on overlapping sounds alone:

hubieran→ huvieran→ uvieran→ uvierã

The second problem with spelling is that, coming out of the Roman alphabet, “v” and “u” can actually overlap or switch spots. It’s possible that “v” will be present but not “u” in spelling, even though they have different sounds. Using the same word, here are some examples:

hubieran→ huvieran→ uvieran→ vuieran

Or, possibly:

hubieran→ uuieran/vvieran

To summarize, if letters can be cut, they will be cut—just like “h” in many of these examples, since it is silent in Spanish. In place of “j” or “ge”/“gi,” one will often find “x,” as in “Xerez”/“Jerez” or “Ximena”/“Jimena.” The letter “y” is often used in place of “ll” or “i.” Sometimes even “n” and “m”—and “f” and “h”—are exchangeable. Whenever a writer decides to save space, he can avoid writing the final “n” on words by simply writing “~” above the last letter, like “uvierã.” When in doubt, don’t panic. Try reading your mystery word out loud to see if it sounds like something that would be familiar if spelled in a modern form.

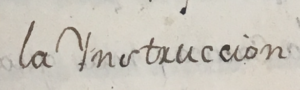

This says “la Ynstruccion” or, pretty clearly from the sounds, “la instrucción.”

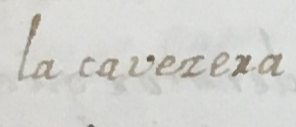

This says “la cavezera” or, in modern spelling, “la cabecera.”

To conclude, the second step for working with Spanish-language texts is to have a familiarity with how the sounds that letters produce can overlap, producing spelling variations. This is related to differences in spoken dialects and the writer’s ability to transfer what they think they hear into text.

This piece is part of The Monster Hiding in the Archives: Spanish Paleography and its Secrets, a series of articles that explores the archival technique of paleography.