I. What is paleography?

The ability to read and study ancient or historical handwriting styles that are no longer recognizable and familiar to modern readers is called paleography. Those of us who want to work with primary sources that have not been transcribed by historians and other diligent scholars must learn this skill, whether the writing is from the 1960s, the 1850s, or the 1300s.

I first wrote a short piece on paleography in the spring of 2016, as part of a collaborative series on this discipline. At the time, I was new to paleography, and most of my successes and failures stemmed from my firsthand experiences, much embarrassment, and many hours struggling with early modern Spanish texts. What struck me the most was that accessing an archive does not always mean that I will be able to actually read the texts that I proposed to read.

After being aware of a few different alphabets that writers could use in their shorthand and knowing how a language’s orthography can vary, the next important item involves the physical and spatial limitations of the writer.

II. Good Paleographic Practices (Continued)

Mechanical issues: medieval minims, page orientation, and writing tools

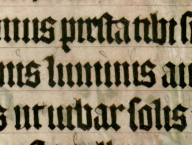

Minim is a word from late Middle English and derives from the Latin word minimus for “smallest.” In calligraphy (the art of writing) and in paleography, it is important to know that this word refers to a single vertical stroke with a writing instrument and that it is the “smallest” writing unit possible. It is primarily a mechanical writing choice, rather than a stylistic one.

Before explaining how the minim works in medieval and some early modern writing, I’d like to direct the reader to other mechanical writing considerations for both medieval and early modern writers. In addition to pages often being rubricated or measured out line by line so that the writer knows how many words will fit on a line (important for writerly economies–saving space on a page in a period when paper/parchment was expensive to produce), the orientation of the page was also important. For medieval scribes, pages did not lay flat on a desk; they were pinned in place nearly vertically with a special type of desk for writing. The monks held their writing tools very differently from how we do now (for more information on these desks, pen-holding, and writing mechanics see de Hamel under the section titled “Paleographic Resources,” which will be released in Part 4). Because of the way the page sat and the way scribes held their pens, it was actually easier for them to write using downstrokes, starting at the top of the letter and moving the quill or pen downwards. This movement from top down creates the minim.

Vertical movement downward, which informed how all medieval letters were written, in particular affected the writing of the letters m, n, i, and u. These four letters could be written exclusively with vertical lines, without any kind of obvious linking markings. In order to read words with many minims (which makes the word difficult to read), it is sometimes necessary to count the number of minims and then do some math to see what letters could make up the word. An “m” has 3 minims, “n” and “u” have 2 minims,” and “i” of course is 1 minim.

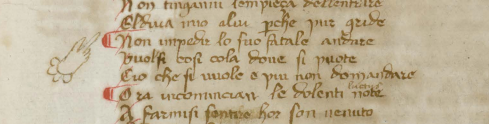

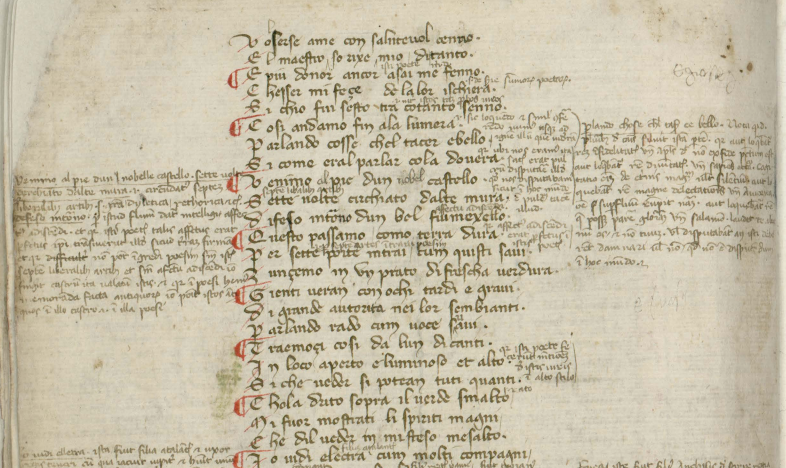

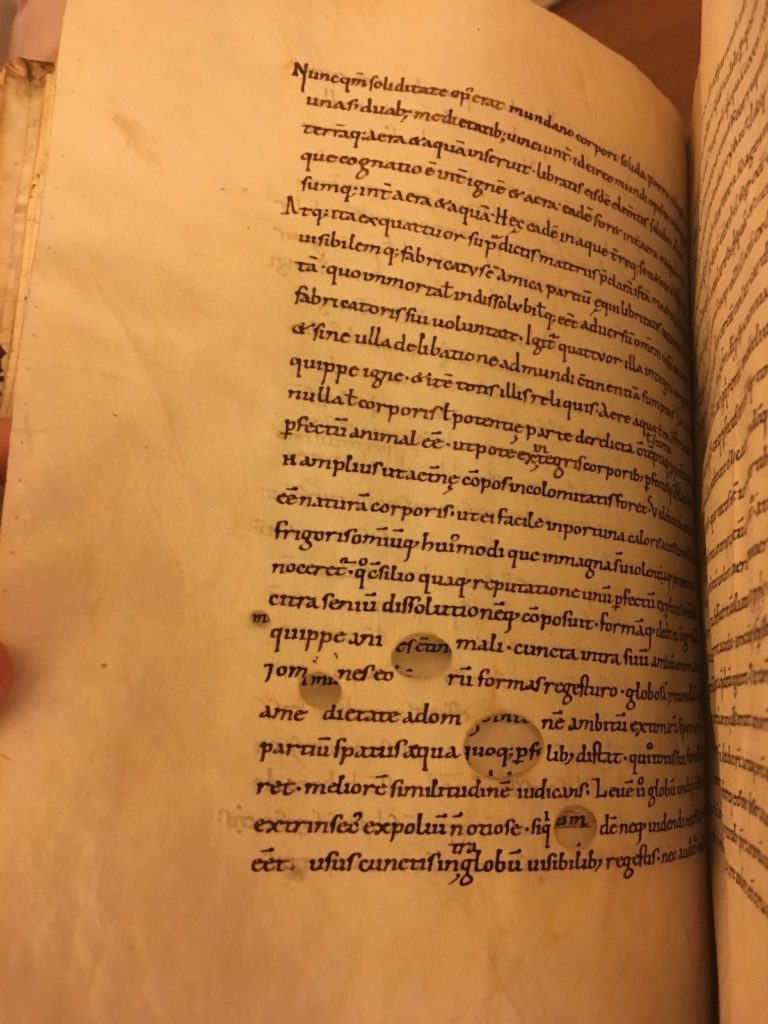

In addition to the difficulty of reading minims, medieval and some early modern handwriting was extremely concerned with paper-saving, as mentioned previously. Because medieval writings are mostly on parchment (untanned animal skin which is laborious and also, quite frankly, gross to produce), writers often did not leave spaces between words in order to save space. They would also cut off words at the ends of lines and start the word where they left off on the next line. That being said, they also left a large amount of space in the margins (or sometimes between lines) for “marginalia” or marginal notes and “interlinear notes.” These notes, which were often added later though sometimes by the scribe himself, direct readers to what was believed to be the important passages and these notes often explained the important parts in more detail. If the scribe could not be bothered to write a note, but still wanted to indicate importance, he would draw a little hand or “manicule” pointing at the important part.

Marginalia, or marginal notes, supplement the main body of the text, which is not only centered on the page but is also written in a larger hand. These notes are important for guiding readers toward deeper textual meanings, offering context, and supporting teachers as they educated their students. Interlinear notes are also faint but present.

In early modern and modern handwriting, with the advent of new types of pens, penmanship, and cheap paper, writing develops more personality and moves away from “paper-saving” strategies. However, it does move more toward “time-saving” strategies, like abbreviations or shorthand. While marginal notes still exist, what becomes more difficult is the writing style used, paired with writerly abbreviations that are not instinctive or naturally recognizable.

To conclude, another important aspect of paleographic work comes down to the mechanical considerations of the scribe or writer, revolving around everything from the writing instrument to paper quality. In Part 4, we will explore how space-saving and time-saving strategies (in addition to phonemic variation), led to the complex development of early modern abbreviations and the “monster hiding in the archives.”

This piece is part of The Monster Hiding in the Archives: Spanish Paleography and its Secrets, a series of articles that explores the archival technique of paleography.