I’ve had the pleasure to read TransLatin Joyce: Global Transmissions in Ibero-American Literature, released in early May 2014 and edited by Brian L. Price, César A. Salgado, and John Pedro Schwartz.

The new edited volume argues for the “TransLatin appeal” of James Joyce. The Irish writer’s fiction has been revisited, reactivated, and repurposed at the intersection of culture, aesthetics, political agendas, and social struggles in key moments in the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America. These Joycean confluences are not restricted to the past tense: TLJ expands the concept of translation to elucidate the never-finished projects of translatin’ Joyce. At the end of the day, the work convinces us that future Joyce scholarship cannot ignore the author’s dynamic emergences in Spanish and Portuguese.

The new edited volume argues for the “TransLatin appeal” of James Joyce. The Irish writer’s fiction has been revisited, reactivated, and repurposed at the intersection of culture, aesthetics, political agendas, and social struggles in key moments in the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America. These Joycean confluences are not restricted to the past tense: TLJ expands the concept of translation to elucidate the never-finished projects of translatin’ Joyce. At the end of the day, the work convinces us that future Joyce scholarship cannot ignore the author’s dynamic emergences in Spanish and Portuguese.

For someone working in Translation Studies, TLJ represents a key intervention in our understanding of how a literary work created in one geographical, political, and historical context can be transmitted and rewritten in another, vastly different one. The “wave theory” perspective adopted by TLJ seeks to account for the “accumulation and disaggregation, sedimentation and erosion” that are an integral part of Joycean movement, which produces “currents and waves displacing energy in nonlinear, unbounded flows” (xiv). By invoking Wave Theory to challenge the idea that we can fit Joyce’s power in Latin America within fixed, territorial boundaries, TLJ provides a model of literary translation/transmission that destabilizes and complicates fictions of directionality, periodization, and determinability .

Far from chronicling the one-sided influence of a universal High Modernism, TLJ’s contributors elucidate how Joyce’s literary afterlife is molded by the discursive backdrop in which his books reappear. Norman Cheadle analyzes how Ulysses surfaced within the complex politics of the Argentine Culture Wars of the 1930s. Details such as whether Argentine writers described Joyce as “Irish” – and, therefore, implicitly affiliated with Catholic nationalists in Argentina – or (accidentally-on-purpose) as “English” weaves literature and literary biography into debates of “neocolonialism and empire, language and nationalism, religion and ideology” (59).

Joycean readings are not only are shaped by social agendas, but also actively set the terms for discursive and political battles. In a 1964 Cuban translation of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man that “corrects” a classic 1926 translation from Spain, the novel takes on the role of protagonist. César Salgado argues that the Edmundo Desnoes’ 1964 Retrato is an anticolonial “detranslation” meant to wrest the text from Eurocentric elitism and to rewrite Joyce/Stephen as an aesthetic forerunner to the intellectual paradigm of the Cuban Revolution. By detranslating – simplifying linguistic flourishes, and at times literally returning the Spanish to English – the text takes on a didactic role informed by leftist ideology. Extratextual ideologies penetrate the translators’ textual choices, which in turn justify those very same ideologies by forging the perfect Joyce: a “subaltern intellectual of the colonial periphery” (122).

Joycean readings are not only are shaped by social agendas, but also actively set the terms for discursive and political battles. In a 1964 Cuban translation of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man that “corrects” a classic 1926 translation from Spain, the novel takes on the role of protagonist. César Salgado argues that the Edmundo Desnoes’ 1964 Retrato is an anticolonial “detranslation” meant to wrest the text from Eurocentric elitism and to rewrite Joyce/Stephen as an aesthetic forerunner to the intellectual paradigm of the Cuban Revolution. By detranslating – simplifying linguistic flourishes, and at times literally returning the Spanish to English – the text takes on a didactic role informed by leftist ideology. Extratextual ideologies penetrate the translators’ textual choices, which in turn justify those very same ideologies by forging the perfect Joyce: a “subaltern intellectual of the colonial periphery” (122).

In the same decade that A Portrait was fashioned into a mold for intellectual and moral formation in Cuba, Ulysses emerged as means of psychologically processing social change in Mexico. José Luis Venegas lays out the ambiguous presence of Ulysses in Gustavo Sainz’s 1969 novel Obsesivos días circulares. To the Mexican novelist, Joyce’s book represents a paradox: it evokes the High Modernist ideal of universal, transcendent art, while at the same time challenging any pretension of narrative coherence that would overlook local struggles and politics. The Joyce enigma served as an especially relevant tool for reflecting on the fragmentation and alienation that Sainz observed in Mexico. Venegas’ essay is a critical case study of how a text’s afterlife casts new light on the source, as a Ulysses-inflected Latin American novel exposes nuanced ambiguities of Joyce’s original work.

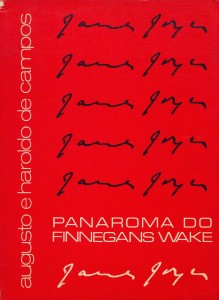

The TransLatin framework analyzes the waves initiated by Joycean texts in the Iberian Peninsula and in Latin America. Although Joyce’s reception in Portugal is documented in John Pedro Schwartz’s essay on Fernando Pessoa’s annotations of Ulysses, Brazil is a country missing from TLJ’s essays. Brazil has seen literary production inflected by Joyce through translation and through affiliated novels (much to the chagrin of Paulo Coelho, as discussed in TLJ’s Introduction). Guimarães Rosa’s Grande Sertão: Veredas – a vast novel that entwines Joycean linguistic enterprise together with Brazil’s literary and cultural traditions – can be fruitfully reread as a TransLatin Joycean work. Similarly, Clarice Lispector’s experimental novels such as Perto do Coração Selvagem (the title of which translates to “near to the wild heart,” a phrase from A Portrait) offer grounds for comparison with other Latin American Joycean projects. Haroldo and Augusto de Campos’ ambitious translation Panorama de Finnegan’s Wake motivates a dialogue with works such as Desnoes’ translation of A Portrait. Whereas Desnoes selected Joyce’s first novel to influence the aesthetic and intellectual priorities of Castro’s regime, the de Campos brothers invoked Joyce’s final and most experimental work as a way of universalizing the “world’s literary patrimony” to be available in Brazil.

The TransLatin framework analyzes the waves initiated by Joycean texts in the Iberian Peninsula and in Latin America. Although Joyce’s reception in Portugal is documented in John Pedro Schwartz’s essay on Fernando Pessoa’s annotations of Ulysses, Brazil is a country missing from TLJ’s essays. Brazil has seen literary production inflected by Joyce through translation and through affiliated novels (much to the chagrin of Paulo Coelho, as discussed in TLJ’s Introduction). Guimarães Rosa’s Grande Sertão: Veredas – a vast novel that entwines Joycean linguistic enterprise together with Brazil’s literary and cultural traditions – can be fruitfully reread as a TransLatin Joycean work. Similarly, Clarice Lispector’s experimental novels such as Perto do Coração Selvagem (the title of which translates to “near to the wild heart,” a phrase from A Portrait) offer grounds for comparison with other Latin American Joycean projects. Haroldo and Augusto de Campos’ ambitious translation Panorama de Finnegan’s Wake motivates a dialogue with works such as Desnoes’ translation of A Portrait. Whereas Desnoes selected Joyce’s first novel to influence the aesthetic and intellectual priorities of Castro’s regime, the de Campos brothers invoked Joyce’s final and most experimental work as a way of universalizing the “world’s literary patrimony” to be available in Brazil.